Surveillance Report #109

TRENDS IN SUBSTANCE USE AMONG REPRODUCTIVE-AGE FEMALES IN THE UNITED STATES, 2002–2015

Megan E. Slater, Ph.D.

Sarah P. Haughwout, M.P.H.

CSR, Incorporated1

4250 N. Fairfax Drive

Suite 500

Arlington, VA 22203

September 2017

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Public Health Service

National Institutes of Health

1 CSR, Incorporated operates the Alcohol Epidemiologic Data System (AEDS) under Contract No. HHSN275201300016C for the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Dr. Rosalind A. Breslow (Division of Epidemiology and Prevention Research) serves as the NIAAA Contracting Officer's Representative on the contract.

HIGHLIGHTS

This surveillance report, prepared by the Alcohol Epidemiologic Data System (AEDS), National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), presents data on substance use among reproductive-age females (ages 15–44) for 2002–2015. This is the second of a series of biennial reports on substance use in this population. Data for this series are compiled from a nationally representative survey, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). Due to methodological changes to the 2015 NSDUH, data for some of the substance use measures in this report are only available through 2014. The following are highlights from the survey for this population.

Alcohol Use (Any Drinking, Binge Drinking, and Heavy Drinking in the Past 30 Days)

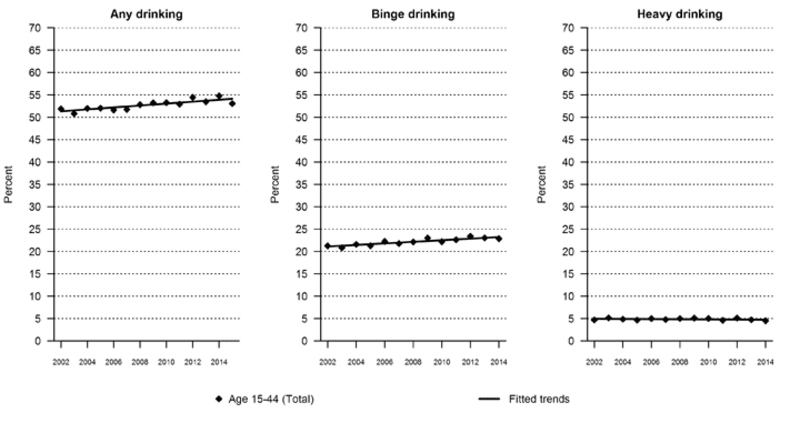

- In 2015, 53.1% of all reproductive-age females reported any drinking, down slightly from the 54.8% that reported any drinking in 2014.

- In 2014, 22.9% reported binge drinking on at least one occasion, and 4.5% reported heavy drinking.

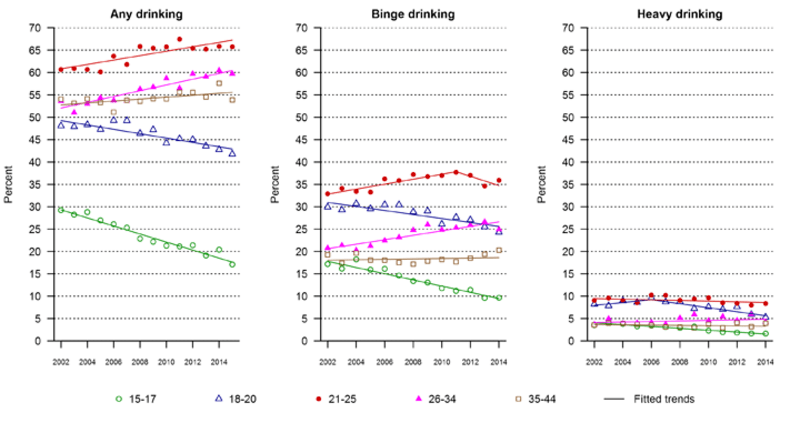

- Between 2002 and 2015, trends show an overall increase in the prevalence of any drinking among females ages 21–44 and a decrease among those ages 15–20.

- Between 2002 and 2014, the prevalence of binge drinking increased among those ages 21–34, decreased among those ages 15–20, and remained stable among those ages 35–44. The prevalence of heavy drinking decreased among those ages 15–20 and remained stable among those ages 21–44 during this period.

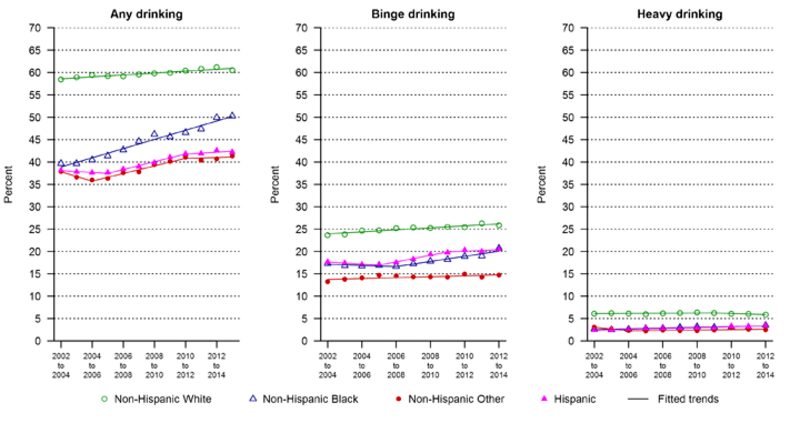

- Any drinking (2002–2015) and binge drinking (2002–2014) increased among all racial/ethnic groups, whereas heavy drinking (2002–2014) increased only among non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics.

- Throughout these periods, the prevalence of any, binge, and heavy drinking remained highest among those ages 21–25 years and among non-Hispanic Whites.

- Among pregnant females overall, any drinking and binge drinking declined between 2002 and 2015 and between 2002 and 2014, respectively.

Substance Use Among Current Drinkers (in the Past 30 Days)

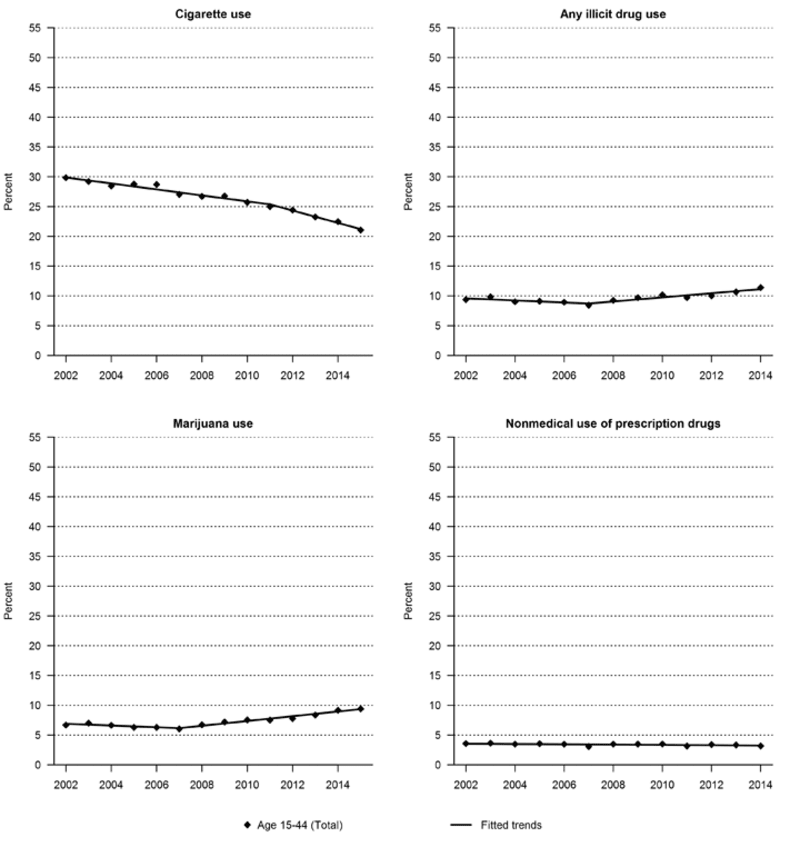

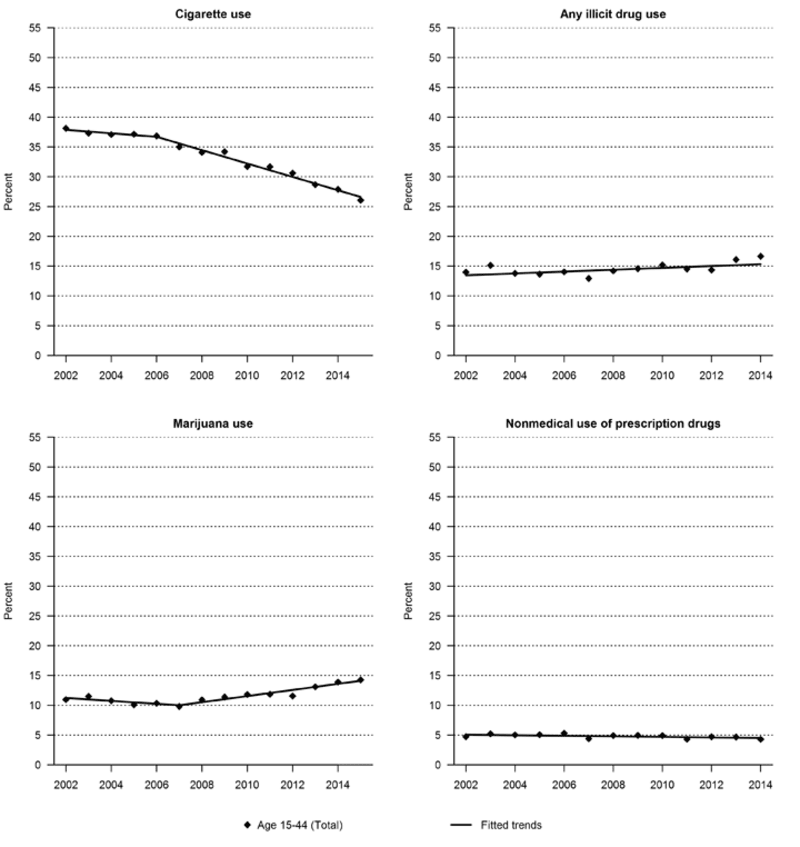

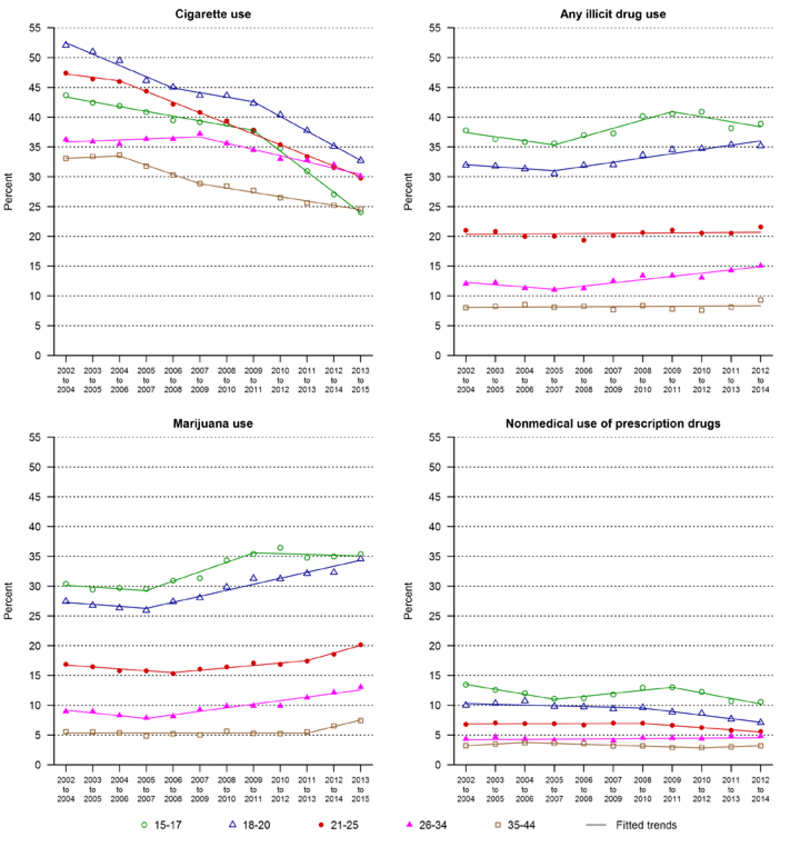

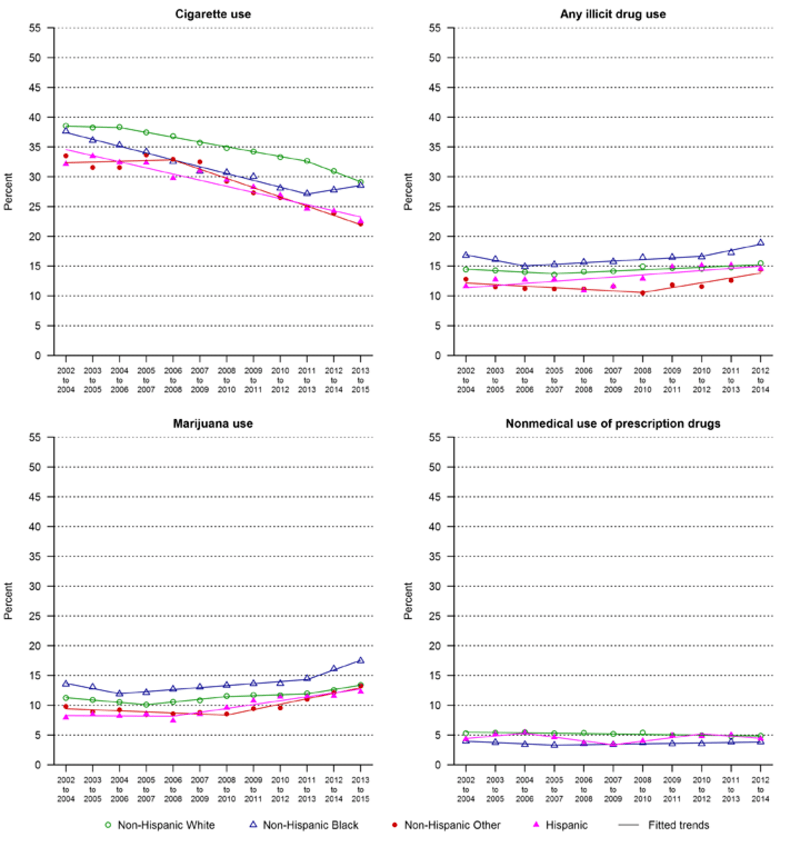

- The prevalence of cigarette use among current drinkers decreased for all age and racial/ethnic groups. Overall, it went from 38.1% in 2002 to 26.1% in 2015. It remained the highest among those ages 18–20 and among non-Hispanic Whites.

- Among current drinkers overall, any illicit drug use and marijuana use increased between 2002 and 2014 and between 2002 and 2015, respectively. Nonmedical use of prescription drugs among current drinkers remained stable between 2002 and 2014.

- Any illicit drug use among current drinkers increased between 2002 and 2014 for those ages 15–20 and 26–34 and for non-Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic Blacks, and Hispanics. Marijuana use among current drinkers increased between 2002 and 2015 for all age and race/ethnic groups. Non-Hispanic Blacks and those ages 15–17 had the highest prevalence of any illicit drug use and marijuana use over the study periods.

- Nonmedical use of prescription drugs among current drinkers remained relatively stable, with small decreases for non-Hispanic Whites and for those ages 18–25 and 35–44.

Alcohol and Illicit Drug Abuse and Dependence (in the Past 12 Months)

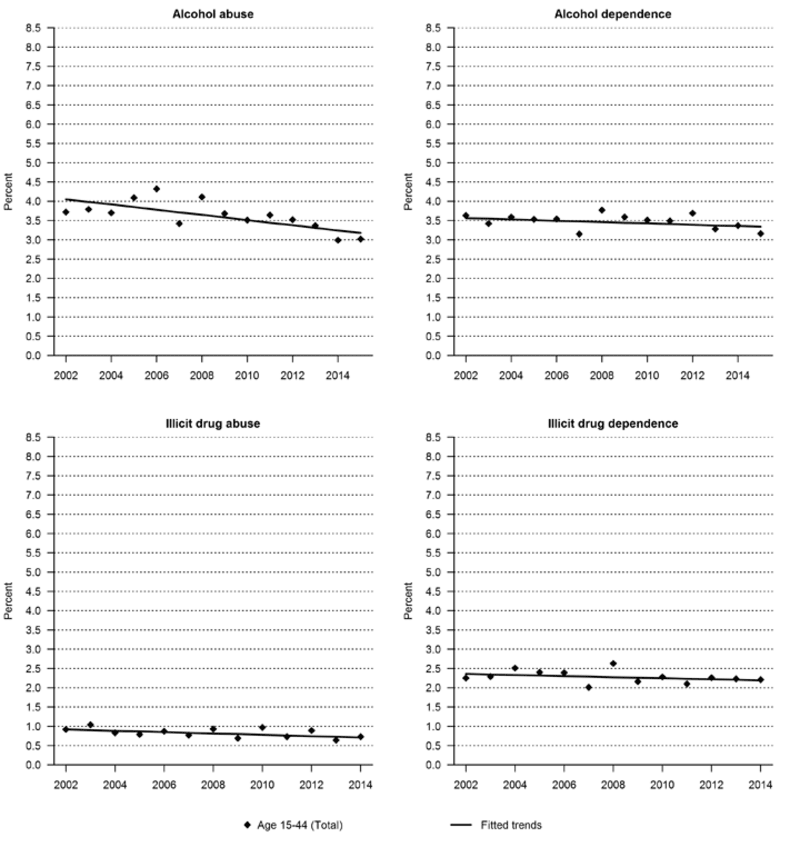

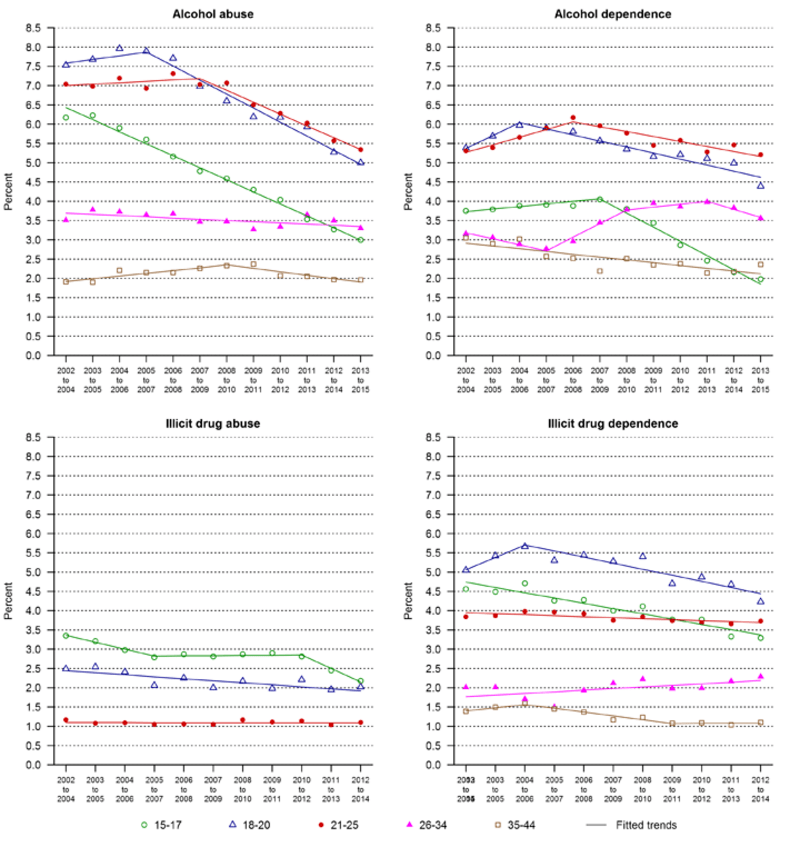

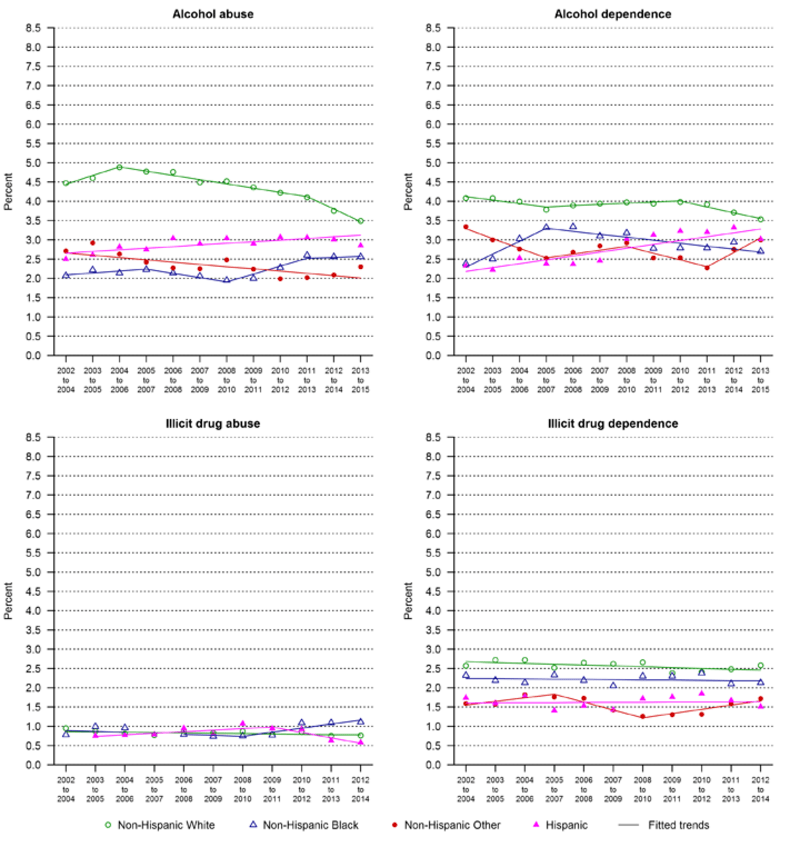

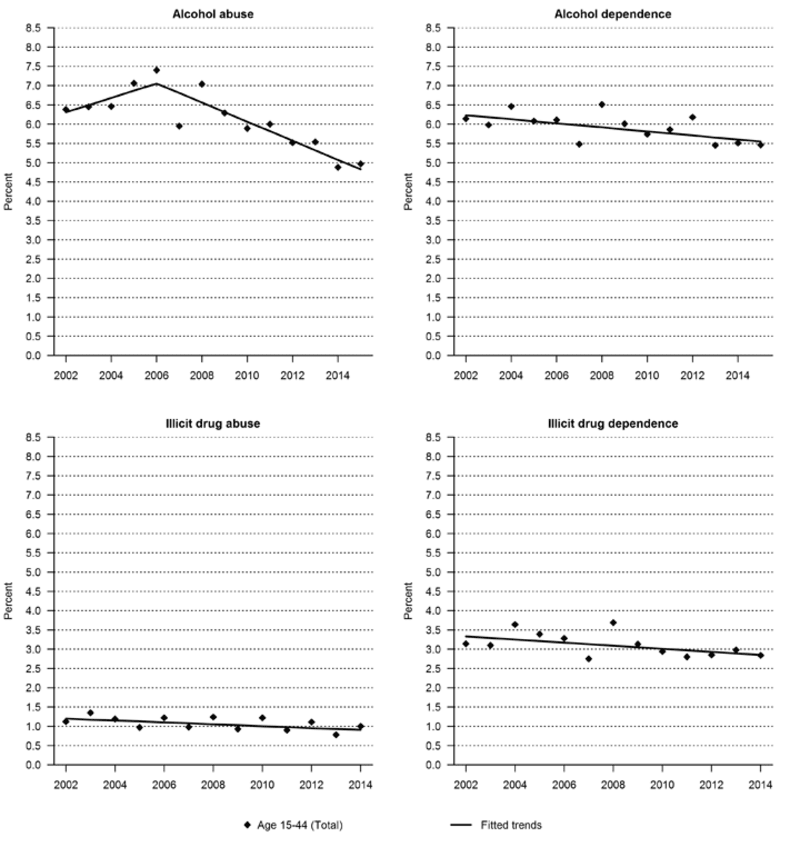

- There was an overall decline in the prevalence of DSM-IV alcohol abuse (2002–2015), alcohol dependence (2002–2015), and illicit drug abuse (2002–2014) among current drinkers.

Treatment for Alcohol and Illicit Drug Use (in the Past 12 Months)

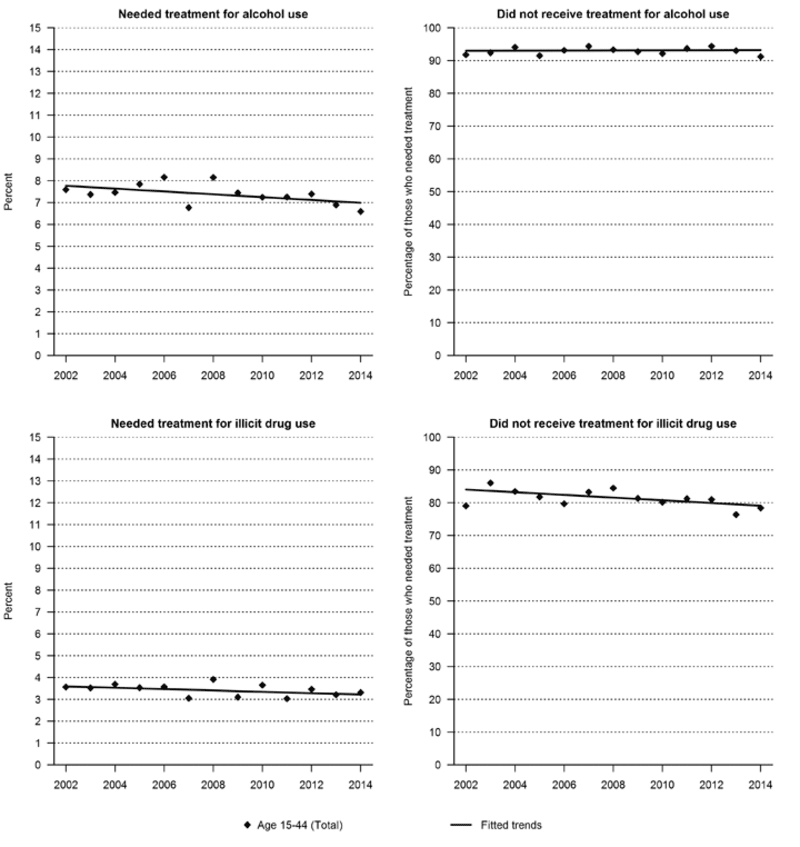

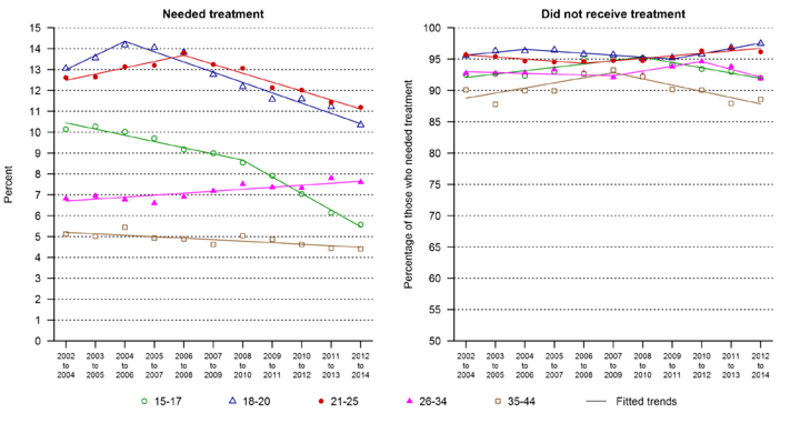

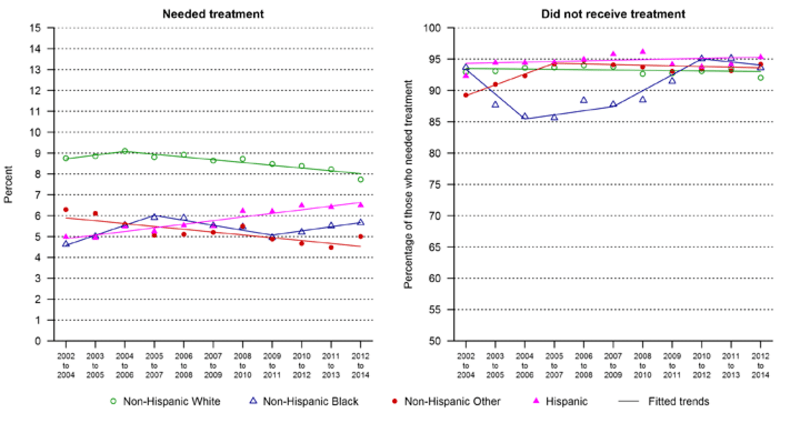

- The percentage of females who needed treatment for alcohol use increased between 2002 and 2014 among Hispanics and those ages 26–34 but decreased among non-Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic others, and those ages 15–25 and 35–44. A large treatment gap has persisted over time, as more than 90% of all those who need treatment for alcohol use did not receive treatment.

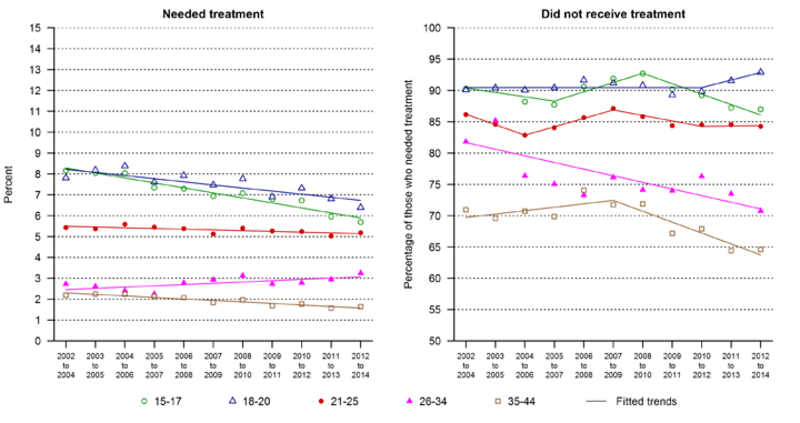

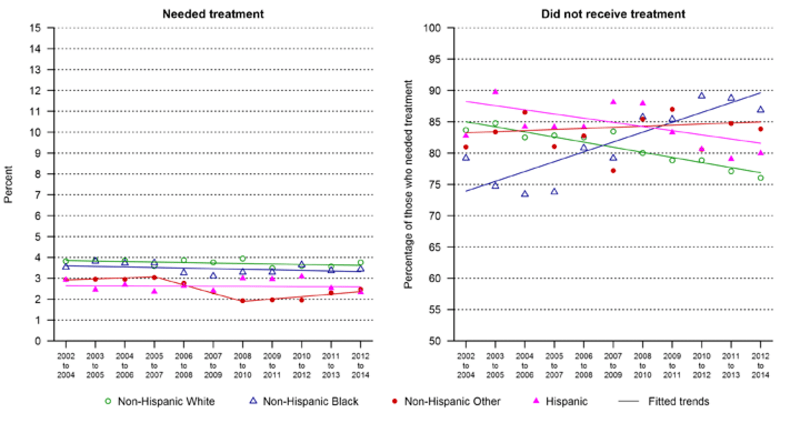

- The percentage of females who needed treatment for illicit drug use decreased between 2002 and 2014 among non-Hispanic others and those ages 15–25 and 35–44, increased among those ages 26–34, and remained stable among all other groups. The treatment gap for illicit drug use decreased among non-Hispanic Whites and those ages 26–44 but increased among non-Hispanic Blacks.

INTRODUCTION

This surveillance report is the second in a series of biennial reports published to monitor substance use trends among reproductive-age females (ages 15–44). This report is prepared by AEDS staff and the Division of Epidemiology and Prevention Research, NIAAA, and is intended to provide information for policymakers, researchers, and others interested in substance use among this population. This information is essential in assessing the progress toward meeting targets set in Healthy People 2020 to increase abstinence from alcohol, cigarettes, and illicit drug use among females during and prior to pregnancy (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS] 2014).

Harmful Effects of Substance Use on Reproductive-age Females

Studies show that for females, rates of substance use are highest among those of reproductive age–53.1%, 21.1%, and 12.2% reported past month alcohol, cigarette, and illicit drug use, respectively, in 2015 (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality [CBHSQ] 2016a, Table 6.74B). Substance use can be even more harmful for females than males, with females experiencing more severe consequences in a shorter period of time and from lesser amounts used (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] 2009b).

Alcohol. Recent evidence indicates that alcohol consumption patterns across the U.S. may be changing. The prevalence of past-year binge drinking among U.S. adults increased from 23% in 2001–2002 to 33% in 2012–2013, which included increases in high-intensity binge drinking (i.e., drinking two or more times the standard gender-specific binge thresholds) (Hingson et al. 2017). While alcohol use is higher among males, research shows that drinking patterns between males and females narrowed between 2002 and 2012, with females reporting increased current and binge drinking (White et al. 2015). Females who consume heavy amounts of alcohol are susceptible to liver and organ damage, cardiomyopathy and myopathy, and brain damage (Hommer et al. 2001; Loft et al. 1987; Urbano-Marquez 1995). Heavy alcohol consumption has also been shown to compromise bone quality and decrease bone density particularly during young adulthood when bones are still developing, therefore increasing susceptibility to osteoporosis (Sampson 2002).

Cigarettes. Smoking cigarettes increases the risk of developing peptic ulcers, Crohn’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and cancers of the lung, cervix, pancreas, and mouth and throat (Cosnes et al. 1996; Karlson et al. 1999; Vineis et al. 2004). Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death among females in the United States, surpassing breast cancer deaths (U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group 2014). Electronic cigarette use is increasing in the United States, with the highest use among females occurring in those of reproductive age (McMillen et al. 2015; Schoenborn and Gindi 2015).

Illicit drugs. Illicit drug use increases the risk of drug-induced death, kidney and liver damage, and infections such as human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis (HHS 2013; Khalsa and Elkashef 2010). Female illicit drug users may also experience menstrual abnormalities including amenorrhea and irregular menstrual cycles (SAMHSA 2009b). Marijuana is the most commonly used illicit drug among reproductive-age females (CBHSQ 2016a, Table 6.71B). Between 2001 and 2013, marijuana use among U.S. adults more than doubled, and attitudes toward marijuana became more permissive (Hasin et al. 2015). States have increasingly begun eliminating restrictions against marijuana use; currently, 29 states and the District of Columbia have legalized medical marijuana use, and 8 of those states have also legalized recreational use (Carnevale et al. 2017). Adverse consequences of marijuana use include impaired memory and respiratory function and an increased risk of developing mental health issues (Block et al. 2002; Hall and Degenhardt 2009; Moore et al. 2005, 2007; Volkow et al. 2014).

Prescription drugs. Studies show that borrowing or sharing prescription medications was more common among young females ages 15–18 than among those ages 14 and under (Daniel et al. 2003) and more common among females ages 18–44 than among those ages 45 and older (Petersen et al. 2008). Opioid use is an increasingly serious public health issue; of the 52,404 drug overdose deaths reported in 2015, 33,091 involved opioids (Rudd et al. 2016). More than a third of reproductive-age females enrolled in Medicaid and more than a quarter of those with private insurance filled an opioid prescription each year during 2008–2012 (Ailes et al. 2015). Risk of depression is also greatest in reproductive-age females, and 15.4% filled a prescription for an antidepressant during 2008–2013 (Dawson et al. 2016). Although many people are under the impression that prescription drugs are safer to use than illegal drugs, misuse of prescription drugs can increase the risk of adverse reactions or accidental overdose and can lead to liver damage, cardiac complications, and neurological dysfunction, as well as adverse social consequences such as engaging in unprotected sex (Benotsch et al. 2010; Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2012; SAMHSA 2009b).

Harmful Effects of Substance Use on Pregnant Females and Their Children

Although substance use is less common among pregnant females, with 9.3%, 13.6%, and 4.7% of pregnant females reporting alcohol, cigarette, and illicit drug use, respectively, in 2015, consequences can be more severe for pregnant females and their unborn children than for nonpregnant females (CBHSQ 2016a, Table 6.74B).

Alcohol. During a 1-month period from 2011–2013, approximately 3.3 million females in the U.S. were at risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy, in which they reported consuming alcohol and having unprotected sex (Green et al. 2016). Alcohol use during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of miscarriage, preterm birth, and abruptio placentae (premature separation of the placenta from the uterus) (Aliyu et al. 2011; Du Toit et al. 2010; SAMHSA 2009b). Fetal development can be disrupted by alcohol use during any stage of pregnancy, leading to complications such as fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD). Infants affected by alcohol can experience lifelong neurobehavioral, cognitive, and physical abnormalities (Bertrand et al. 2005; Chiriboga 2003; Feldman et al. 2012; Warren et al. 2011). Although symptoms may vary due to a wide range of effects, common features of FASD include facial dysmorphia, maxillary hypoplasia, and stunted growth (Bertrand et al. 2005; Riley et al. 2011).

Cigarettes. Females who smoke cigarettes not only have increased difficulty in conceiving but also can have increased chances of experiencing a miscarriage. Presence of nicotine in the placenta has been associated with low birth weight and small growth during gestational age, as well as long-term cognitive effects (Ko et al. 2014; McHugh et al. 2014; Shiono et al. 1995). Research has found that pregnant females are more likely to consider electronic cigarettes as safer than traditional cigarettes; however, the presence of nicotine can still lead to dangerous birth outcomes (Kahr et al. 2015; Mark et al. 2015).

Illicit drugs. Pregnant females using illicit drugs may increase their risk of miscarriage, premature rupture of membranes, preeclampsia, and abruptio placentae. There is also an increased risk of preterm birth, intrauterine death, and fetal heart abnormalities (Bada et al. 2005; Little et al. 1989; SAMHSA 2009b; Shiono et al. 1995). Several studies on the consequences of prenatal marijuana use have shown impaired fetal growth and lower cognitive development among exposed children (Calvigioni et al. 2014; Goldschmidt et al. 2004; Marroun et al. 2009). Chabarria and colleagues (2016) found that among pregnant female marijuana users, 48% concurrently smoked cigarettes, significantly increasing perinatal adverse outcomes.

Prescription drugs. Pregnant females using opioids, tranquilizers, and stimulants risk giving birth prematurely, with increased risk of fetal heart defects and fetal death (Bracken and Holford 1981; Broussard et al. 2011). Maternal opioid use is becoming an increasingly serious issue, with an annual average of 21,000 pregnant women reporting opioid misuse from 2007–2012, with higher misuse among those ages 15–25 (Smith and Lipari 2017). In utero exposure to opioids can cause severe negative neonatal outcomes, leading to infants who have drug-withdrawal complications. Numerous studies have shown that there has been an increase in the number of infants born with neonatal withdrawal syndrome in the United States, particularly in rural communities (Pan and Yi 2013; Patrick et al. 2012, 2015; Tolia et al. 2015; Villapiano et al. 2017). Infants born with neonatal withdrawal syndrome experience hyperactive reflexes, increased muscle tone, and slow weight gain (American Academy of Pediatrics 1998; Hudak et al. 2012). Furthermore, certain selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) prescribed for depression can lead to birth defects including anencephaly, congenital heart disorders, gastroschisis, and craniosynostosis, even when taken early in pregnancy (Reefhuis et al. 2015).

Concurrent Alcohol and Drug Use

Studies show that females who smoke cigarettes or use marijuana are also more likely to drink alcohol or use other drugs (Drobes 2002; Midanik et al. 2007; Tsai et al. 2010). Concurrent alcohol and drug use is dangerous due to the additive effects, leading to more adverse outcomes such as overdose, and increased chances of developing substance use disorders (SAMHSA 2009a; World Health Organization [WHO] 2014). When combined with alcohol, opioid use can lead to overdoses due to respiratory depression. Opioids are the most commonly used medication among females ages 21–34 in the increasing number of alcohol- and drug-related emergency department visits (Castle et al. 2016; WHO 2014). Midanik and colleagues (2007) found that concurrent use of alcohol and drugs among females was significantly related to the prevalence of alcohol dependence, depression, and negative social consequences, including relationship, health, and work issues, therefore increasing the need for treatment.

Treatment

Recent reporting shows that males and females who need treatment for substance use seek treatment at similarly low rates. However, females encounter unique barriers when seeking treatment, such as societal stigma toward female users (CBHSQ 2016a, Table 5.60B; Hecksher and Hesse 2009). Studies show that females are more likely to report shame and embarrassment upon treatment entry and are less likely to report substance use as the root of their problems (Green 2006; Thom 1987). Pregnant females also report fear of prosecution and loss of child custody as reasons to not seek treatment (Bishop et al. 2017). Pregnant females in particular experience affordability issues due to the additional costs of bearing a child (Jackson and Shannon 2012; SAMHSA 2009b). Racial/ethnic minority females experience further barriers toward treatment, including less access, lower quality of services, language differences, and mistrust of the healthcare system (Alvidrez 1999; Davis and Ancis 2012; Greenfield et al. 2007).

The majority of alcohol consumption reported by pregnant females occurs during their first trimester (CBHSQ 2016a, Table 6.76B). In a study examining alcohol use in unplanned pregnancies, 56% of females reported alcohol use during the month before they knew they were pregnant (Roberts et al. 2014). Chapman and Wu (2013) found that adolescent mothers in particular reported greater substance use before pregnancy compared with other adolescent females. Because many females are not aware that they are pregnant until several weeks or even months into pregnancy, it is important to examine the trends of substance use among all reproductive-age females. Though females tend to decrease their substance use after they become aware that they are pregnant, the embryo may be affected by substance exposure at any time.

DATA SOURCE

National Survey on Drug Use and Health

Data for this report are drawn from NSDUH, a publically available dataset conducted by SAMHSA since 1971. The survey represents 98% of the noninstitutionalized civilian population ages 12 and older, excluding homeless, institutionalized, and active duty military populations. Participants are selected by an independent multistage area probability sample design, with oversampling of youth and young adults to achieve approximately equal distribution of three age groups: ages 12–17, 18–25, and 26 and older. NSDUH is administered in a face-to-face setting at the participant’s home. Due to the sensitivity of the survey topics and to ensure confidentiality and better accuracy of reporting, NSDUH uses audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) to ask most survey questions. Respondents answer questions on current pregnancy status, past 30-day substance use (including alcohol, cigarettes, and illicit drugs), and past year substance abuse, dependence, and treatment.

Study Population and Subgroups

This surveillance report tracks substance use among females as well as cigarette and illicit drug use among female current drinkers ages 15 to 44. This is the same age range that WHO uses to define reproductive-age females as well as the range that the Healthy People 2020 report uses to monitor the prevalence of substance use during and prior to pregnancy (HHS 2014; WHO 2013). Key substance use measures are presented overall and by age group (15–17, 18–20, 21–25, 26–34, and 35–44) and by race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic Blacks, non-Hispanic others, and Hispanics). Because of small sample sizes of pregnant females, only a subset of substance use measures (any drinking and binge drinking) have reliable prevalence estimates and are presented by pregnancy status.

Surveillance Timeframe

Starting in 2002, NSDUH made several methodological changes that represented a new baseline for the following years. Changes included paying a $30 incentive to participants, implementing improved data quality-control measures, and using new population data from the 2000 decennial census. In 2015, NSDUH made additional methodological changes to the survey questionnaire that represented a new baseline for a subset of the substance use measures included in this report. Changes included numerous revisions to the illicit and prescription drug use modules and a revision to the definition of binge drinking among females (revised from 5 or more drinks on an occasion to 4 or more drinks on an occasion to align with current Federal definitions) (CBHSQ 2016b). Therefore, this report presents data from 2002 to 2015 for measures that were unaffected by the aforementioned changes and presents data from 2002 to 2014 (i.e., 2015 data is listed as “nc” [not comparable due to methodological changes] in the tables) for measures that were affected by the changes.

METHODS

This surveillance report tracks substance use among reproductive-age females ages 15–44 from 2002 to the latest comparable year available in the NSDUH survey, 2014 or 2015.

Definitions

The report presents trend data on any/current, binge, and heavy drinking; cigarette use, any illicit drug use, marijuana use, and nonmedical use of prescription drugs; and alcohol/illicit drug dependence, abuse, and treatment. Definitions of these measures are as follows:

- Any/current drinking

- One or more drinks of an alcoholic beverage in the past 30 days

- Binge drinking

- Four or more drinks on the same occasion (at the same time or within a couple of hours of each other) on at least 1 day in the past 30 days

- Heavy drinking

- Four or more drinks on the same occasion on each of 5 or more days in the past 30 days

- Cigarette use

- Smoked part or all of a cigarette in the past 30 days

- Any illicit drug use

- Use of any illicit drug (i.e., marijuana/hashish, cocaine/crack, heroin, hallucinogens, inhalants, pain relievers, tranquilizers, stimulants, and sedatives) in the past 30 days

- Marijuana use

- Use of marijuana (including hashish) in the past 30 days

- Nonmedical use of prescription drugs

- Use of any prescription drug (i.e., pain relievers, tranquilizers, stimulants, and sedatives) in the past 30 days that was not prescribed for the respondent or that the respondent took only for the experience or feeling it caused

- Alcohol/Illicit drug dependence

- Positive response to three or more of the following DSM-IV criteria (all pertain to the past 12 months):

- Spent a great deal of time over a period of a month getting, using, or getting over the effects of the substance

- Was unable to keep set limits on substance use or used more often than intended

- Needed to use substance more than before to get desired effects or noticed that using the same amount had less effect than before

- Was unable to cut down or stop using the substance when desired to or attempted to do so

- Continued to use substance even though it was causing problems with emotions, nerves, mental health, or physical health

- Reduced or gave up participation in important activities due to substance use

- Experienced substance-specific withdrawal symptoms at one time that lasted for longer than a day after cutting back or stopping use of the substance

- Positive response to three or more of the following DSM-IV criteria (all pertain to the past 12 months):

- Alcohol/Illicit drug abuse

- Had positive response to one or more of the following DSM-IV criteria and was not dependent upon the substance of interest (all pertain to the past 12 months):

- Had serious problems due to substance use at home, work, or school

- Used substance regularly and then did something where substance use might have put the respondent in physical danger

- Used substances that caused actions that repeatedly got the respondent in trouble with the law

- Had problems caused by substance use with family or friends and continued to use substance

- Had positive response to one or more of the following DSM-IV criteria and was not dependent upon the substance of interest (all pertain to the past 12 months):

- Needed treatment for alcohol/illicit drug use

- Meet any one of the following criteria:

- Was dependent on substance of interest in the past 12 months

- Abused substance of interest in the past 12 months

- Received treatment for substance use at a specialty facility in the past 12 months including a hospital (inpatient), rehabilitation facility (in- or outpatient), or mental health center

- Meet any one of the following criteria:

- Did not receive treatment for alcohol/illicit drug use (among those who needed treatment)

- Did not receive treatment for substance use (among those who needed treatment) at a specialty facility in the past 12 months, including a hospital (inpatient), rehabilitation facility (in- or outpatient), or mental health center

Analyses

Analyses in this report are mainly descriptive and are presented as nationally representative prevalence estimates. In the figures, trends in prevalence are represented by segmented lines that were fitted using joinpoint (piecewise) regression models (Kim et al. 2000). Data are presented overall and by age, race and Hispanic origin (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic other, and Hispanic), and pregnancy status. Three-year moving averages are used for tracking certain substance use measures to minimize data suppression problems for groups with small sample sizes and to avoid large random fluctuations in the estimates.

To enable readers to assess the precision of the estimates provided, each estimate in the tables is accompanied by a value for the standard error of the estimate (labeled S.E.). Multiplying the standard error by 1.96 provides a margin of error above and below each estimate. This range defines a 95-percent confidence interval that will have a 95-percent chance of including the true value being estimated. Estimates with very large standard errors can be extremely unreliable. The reliability of estimates (r) was assessed using the relative standard error (RSE), computed as RSE=100 × (SE(r)/r). Following the recommendations of the National Center for Health Statistics (Klein et al. 2002), estimates with RSE greater than 17.5% were considered of low reliability and are suppressed in the tables and figures.

We present results from secondary data analysis for NSDUH data, since publicly available reports on these surveys do not cover all the indicators, categories, and age groupings applicable to this report. Prevalence estimates from the NSDUH included in this report may differ slightly from those presented in reports issued by SAMHSA, because SAMHSA analysts use a restricted-use dataset for their analyses.

Limitations

Trend break. Due to the previously mentioned methodological changes to the 2015 NSDUH, a trend break between 2014 and 2015 exists for more than half of the substance use measures included in this report. In other words, estimates before 2015 are not comparable with estimates reported in 2015 and beyond for the measures affected by the break. Therefore, this issue affects both current and future iterations of this surveillance report, with 2015 representing a new baseline for tracking future trends in certain measures of substance use.

Sample sizes. Insufficient sample sizes led to unreliable estimates and data suppression for some measures among small subpopulations in this surveillance report. Compared with the reports issued by SAMHSA, this surveillance report had smaller denominators, and therefore more data suppression, due primarily to the inclusion of estimates among current drinkers rather than the estimates among the total female population. For example, among current drinkers ages 35–44, illicit drug dependence data was suppressed for one 3-year moving average, and illicit drug abuse data was suppressed for all time points. In addition, certain race categories (e.g., American Indian and Asian) were too small to be presented separately in this report, so they were combined into one category (i.e., non-Hispanic other) to represent the full population. As previously mentioned, small sample sizes among pregnant females led to complete data suppression for most of the measures.

Definitions. Another limitation is that data sources use different definitions for some of the measures included in this report. NIAAA defines binge drinking for females as consuming 4 or more drinks on at least 1 occasion in the past 30 days, whereas NSDUH previously (prior to 2015) defined it as consuming 5 or more drinks in the same time period. Because of this higher cutoff, NSDUH may underestimate (by NIAAA standards) the amount of binge drinking that occurred among females prior to 2015 by not including those who consume 4 drinks. NIAAA defines heavy or at-risk drinking among females as consuming more than 3 drinks on any day, or more than 7 drinks per week. Also prior to 2015, NSDUH defined heavy drinking as drinking 5 or more drinks on the same occasion on 5 or more days in the past 30 days. Using this definition, over- or underestimation of heavy drinking depends on the prevalence of various drinking patterns in the population (e.g., weekend binge drinking and daily light-to-moderate drinking) and the time period for which respondents are asked to recall their drinking (e.g., past week or past month). Because no detailed drinking information was available in the NSDUH public-use data for adjusting the definitions of binge drinking and heavy drinking so that they would match those set by NIAAA, the prevalence of these 2 drinking measures in this surveillance report will follow pre-2015 NSDUH definitions by default, rather than NIAAA definitions.

Underreporting. Due to the personal nature of the questions regarding substance use, some respondents may underreport their use. NSDUH corrects for this by using ACASI to ask most of the survey questions. By using ACASI over face-to-face interviews, the levels of honest reporting, privacy, and confidentiality increase. For substance use, demographic, and other key variables, NSDUH replaces missing values by imputation methodology, using predictive mean neighborhoods (CBHSQ 2016b). To increase the usable sample size, imputed values were used wherever possible.

Generalizability. NSDUH does not collect data from the homeless, institutionalized, or active duty military populations, as the survey is administered in the participant’s home. Therefore, results from this surveillance report cannot be generalized to these populations.

REFERENCES

Ailes, E.C.; Dawson, A.L.; Lind, J.N.; Gilboa, S. M.; Frey, M.T.; Broussard, C.S.; and Honein, M.A. Opioid prescription claims among women of reproductive age—United States, 2008–2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 64(2): 37–41, 2015.

Aliyu, M.H.; Lynch, O.; Nana, P.N.; Alio, A.P.; Wilson, R.E.; Marty, P.J.; Zoorob, R.; and Salihu, H.M. Alcohol consumption during pregnancy and risk of placental abruption and placenta previa. Maternal and Child Health Journal 15(5): 670–676, 2011.

Alvidrez, J. Ethnic variations in mental health attitudes and service use among low-income African American, Latina, and European American young women. Community Mental Health Journal 35(6): 515–530, 1999.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Neonatal withdrawal. Pediatrics 101(6): 1079–1088, 1998.

Bada, H.S.; Das, A.; Bauer, C.R.; Shankaran, S.; Lester, B.M.; Gard, C.C.; Wright L.L; Lagasse, L.; and Higgins, R. Low birth weight and preterm births: etiologic fraction attributable to prenatal drug exposure. Journal of Perinatology 25(10): 631–637, 2005.

Benotsch, E.G.; Koester, S.; Luckman, D.; Martin, A.M.; and Cejka, A. Non-medical use of prescription drugs and sexual risk behavior in young adults. Addictive Behaviors 36(1–2): 152–155, 2010.

Bertrand, J.; Floyd, L.L.; and Weber, M.K. Guidelines for identifying and referring persons with fetal alcohol syndrome. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 54(RR-11): 1–14, 2005.

Bishop, D.; Borkowski, L.; Couillard, M.; Allina, A.; Baruch, S.; and Wood, S. Pregnant Women and Substance Use: Overview of Research & Policy in the United States. Washington, DC: George Washington University, Milken Institute School of Public Health, Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health, 2017.

Block, R.I.; O’Leary, D.S.; Hichwa, R.D.; Augustinack, J.C.; Ponto, L.L.B.; Ghoneim, M.M.; Arndt, S.; Hurtig, R.R.; Watkings, G.L.; Hall, J.A.; Nathan, P.E.; and Andreasen, N.C. Effects of frequent marijuana use on memory-related regional cerebral blood flow. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior 72: 237–250, 2002.

Bracken, M.B., and Holford, T.R. Exposure to prescribed drugs in pregnancy and association with congenital malformations. Obstetrics & Gynecology 58(3): 336–344, 1981.

Broussard, C.S.; Rasmussen, S.A.; Reefhuis, J.; Friendman, J.M.; Jann, M.W.; Riehle-Colarusso, T.; and Honein, M.A. Maternal treatment with opioid analgesics and risk for birth defects. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 23(10): 931.e1–941, 2014.

Calvigioni, D.; Hurd, Y.L.; Harkany, T.; and Keimpema, E. Neuronal substrates and functional consequences of prenatal cannabis exposure. Children and Youth Services Review 35(5): 806–815, 2013.

Carnevale, J.T.; Kagan, R.; Murphy, P.J.; and Esrick, J. A practical framework for regulating for-profit recreational marijuana in US States: Lessons from Colorado and Washington.International Journal of Drug Policy 42: 71–85, 2017.

Castle I.J.; Dong, C.; Haughwout. S.P.; and White, A.M. Emergency department visits for adverse drug reactions involving alcohol: United States, 2005 to 2011.Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 40(9): 1913–1925, 2016.

Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2016a. Available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015.pdf.

Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Methodological Summary and Definitions. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2016b. Available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-MethodSummDefsHTML-2015/NSDUH-MethodSummDefsHTML-2015/NSDUH-MethodSummDefs-2015.htm#secc.

Chabarria, K.C.; Racusin, D.A.; Antony, K.M.; Kahr, M; Suter, M.A.; Mastrobattista, J.M.; and Aagaard, K.M. Marijuana use and its effects in pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 215(4): 506.e1–506.e7, 2016.

Chapman, S.L.C., and Wu, L-T. Substance use among adolescent mothers: A review. Children and Youth Services Review 35(5): 806–815, 2013.

Chiriboga, C.A. Fetal alcohol and drug effects. Neurologist 9(6): 267–279, 2003.

Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 538: Nonmedical use of prescription drugs. Obstetrics & Gynecology 120(4): 977–982, 2012.

Cosnes, J.; Carbonnel, F.; Beaugerie, L.; Le Quintrec, Y.; and Gendre, J.P. Effects of cigarette smoking on the long-term course of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 110(2): 424–431, 1996.

Daniel, K.L; Honein, M.A.; and Moore, C.A. Sharing prescription medication among teenage girls: Potential danger to unplanned/undiagnosed pregnancies. Pediatrics 111: 1167–1170, 2003.

Davis, T.A., and Ancis, J. Look to the relationship: A review of African American women substance users’ poor treatment retention and working alliance development. Substance Use & Misuse 47(6): 662–672, 2012.

Dawson, A.L.; Ailes, E.C.; Gilboa, S.M.; Simeone, R.M.; Lind, J.N.; . . . Honein, M.A. Antidepressant prescription claims among reproductive-aged women with private employer-sponsored insurance —United States 2008–2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016.

Drobes, D.J. Concurrent alcohol and tobacco dependence: mechanisms and treatment. Alcohol Research & Health 26: 136–142, 2002.

Du Toit, M.M; Smith, M.; and Odendaal, H.J. The role of prenatal alcohol exposure in abruptio placentae. South African Medical Journal 100(12): 832–835, 2010.

Feldman, H.S.; Jones, K.L.; Lindsay, S.; Slymen, D.; Klonoff-Cohen, H.; Kao, K.; Rao, S.; and Chambers, C. Prenatal alcohol exposure patterns and alcohol-related birth defects and growth deficiencies: a prospective study. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 36(4): 670-676, 2012.

Goldschmidt, L.; Richardson, G.A.; Cornelius, M.D.; and Day, N.L. Prenatal marijuana and alcohol exposure and academic achievement at age 10. Neurotoxicology and Teratology 26(4): 521–532, 2004.

Green, C.A. Gender and use of substance abuse treatment services. Alcohol Research & Health 29(1): 55–62, 2006.

Green, P.P.; McKnight-Eily, L.R.; Tan, C.H.; Mejia, R.M.; and Denny, C.H. Vital signs: Alcohol-exposed pregnancies—United States, 2011–2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016.

Greenfield, S.F.; Brooks, A.J.; Gordon, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Kropp, F.; McHugh, R.K.; Lincoln, M.; Hien, D.; and Miele, G.M. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: A review of the literature. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 86(1): 1–21, 2007.

Hall, W., and Degenhardt, L. Adverse health effects of non-medical cannabis use. Lancet 374(9698): 1383–1391, 2009.

Hasin, D.S;, Saha, T.D.; Kerridge, B.T.; Goldstein, R.B.; Chou, S.P.; Zhang, H.; . . . Grant, B.F. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States between 2001–2002 and 2012–2013. JAMA Psychiatry 72(12): 1235–1242, 2015.

Hecksher, D., and Hesse, M. Women and substance use disorders. Mens Sana Monographs 7(1): 50–62, 2009.

Hingson, R.W.; Zha, W.; and White, A.M. Drinking beyond the binge threshold: Predictors, consequences, and changes in the U.S. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 52(6): 717–727, 2017.

Hommer, D.; Momenana, R.; Kaiser, E.; and Rawlings, R. Evidence for a gender-related effect of alcoholism on brain volumes. American Journal of Psychiatry 158(2): 198–204, 2001.

Hudak, M. L., and Tan, R. C. Committee on Drugs, and the Committee on Fetus and Newborn, American Academy of Pediatrics. Neonatal drug withdrawal. Pediatrics 129(2): e540–560, 2012.

Jackson, A., and Shannon, L. Barriers to receiving substance abuse treatment among rural pregnant women in Kentucky. Maternal and Child Health Journal 16(9): 1762–1770, 2012.

Kahr, M.K.; Padgett, S.; Shope, C.D.; Griffin, E.N.; Xie, S.S.; Gonzalez, P.J.; . . . Suter, M A. A qualitative assessment of the perceived risks of electronic cigarette and hookah use in pregnancy. BMC Public Health 15: 1273, 2015.

Karlson, E.W.; Lee, I.M.; Cook, N.R.; Manson, J.E.; Buring, J.E.; and Hennekens, C.H. A retrospective cohort study of cigarette smoking and risk of rheumatoid arthritis in female health professionals. Arthritis & Rheumatology 42(5): 910–917, 1999.

Khalsa, J.H., and Elkashef, A. Interventions for HIV and hepatitis C virus infections in recreational drug users. Clinical Infectious Diseases 50(11): 1505–1511, 2010.

Kim, H.J.; Fay, M.P.; Feuer, E.J.; and Midthune, D.N. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Statistics in Medicine 19(3): 335–351, 2000.

Klein, R.J.; Proctor, S.E.; Boudreault, M.A.; and Turczyn, K.M. Healthy People 2010 criteria for data suppression. Statistical Notes No. 24. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2002.

Ko, T.-J.; Tsai, L.-Y.; Chu, L.-C.; Yeh, S.-J.; Leung, C.; Chen, C.-Y.; Chou, H.-C.; Tsao, P.-N.; Chen, P.-C.; and Hsieh, W.-S. Parental smoking during pregnancy and its association with low birth weight, small for gestational age, and preterm birth offspring: a birth cohort study. Pediatrics and Neonatology 55(1): 20–27, 2014.

Little, B.B.; Snell, L.M.; Klein, V.R.; and Gildtrap, L.C. Cocaine abuse during pregnancy: Maternal and fetal implications. Obstetrics & Gynecology 73(2): 157–160, 1989.

Loft, S.; Olesen, K.L.; and Dossing, M. Increased susceptibility to liver disease in relation to alcohol consumption in women. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 22(20): 1251–1256, 1987.

Mark, K.S.; Farquhar, B.; Chisolm, M.S.; Coleman-Cowger, V.H.; and Terplan, M. Knowledge, attitudes, and practice of electronic cigarette use among pregnant women. Journal of Addiction Medicine 9(4): 266–272, 2015.

Marroun, H.E.; Tiemeier, H.; Steegers, E.A.P.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; Hofman, A.; Verhulst, F.C.; Brink, W.; and Huizink, A.C. Intrauterinecannabis exposure affects fetal growth trajectories: The Generation R Study. Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 48(12): 1173–1181, 2009.

McHugh, R.K.; Wigderson, S.; and Greenfield, S.F. Epidemiology of substance use in reproductive-age women. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America 41(2): 177–189, 2014.

McMillen, R.C.; Gottlieb, M.A.; Shaefer, R.M.; Winickoff, J.P.; and Klein, J.D. Trends in electronic cigarette use among U.S. adults: Use is increasing in both smokers and nonsmokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 17(10): 1195–1202, 2015.

Midanik, L.T.; Tam, T.W.; and Weisner, C. Concurrent and simultaneous drug and alcohol use: Results of the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 90(1): 72–80, 2007.

Moore, B.A.; Augustson, E.M.; Moser, R.P.; and Budney, A.J. Respiratory effects of marijuana and tobacco use in a U.S. sample. Journal of General Internal Medicine 20(1): 33–37, 2005.

Moore, T.H.; Zammit, S.; Lingford-Hughes, A.; Barnes, T.R.; Jones, P.B.; Burke, M.; and Lewis, G. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic of affective mental health outcomes: A systematic review. Lancet 370(9584): 319–328, 2007.

Pan, I-J., and Yi, H.Y. Prevalence of hospitalized live births affected by alcohol and drugs and parturient women diagnosed with substance abuse at liveborn delivery: United States, 1999–2008. Maternal and Child Health Journal 17(4): 667–676, 2013.

Patrick, S.W.; Schumacher, R.E.; Benneyworth, B.D.; Krans, E.E.; McAllister, J.M.; and Davis, M.M. Neonatal abstinence syndrome and associated health care expenditures: United States, 2000–2009. Journal of the American Medical Association 307(18): 1934–1940, 2012.

Patrick, S.W.; Davis, M.M.; Lehman, C.U.; and Cooper, W.O. Increasing incidence and geographic distribution of neonatal abstinence syndrome: United States 2009 to 2012. Journal of Perinatology 35(8): 667, 2015.

Petersen, E.E.; Rasmussen, S.A.; Daniel, K.L.; Yazdy, M.M.; and Honein, M.A. Prescription medication borrowing and sharing among women of reproductive age. Journal of Women's Health 17(7): 1073–1080, 2008.

Reefhuis, J.; Devine, O.; Friedman, J.M.; Louik, C.; and Honein, M.A. Specific SSRIs and birth defects: bayesian analysis to interpret new data in the context of previous reports. British Medical Journal 351, 2015.

Riley, E.P.; Infante, M.A.; and Warren, K.R. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: An overview. Neuropsychology Review 21(2): 73–80, 2011.

Roberts, S.C.M.; Wilsnack, S.C.; Foster, D.G.; and Delucchi, K.L. Alcohol use before and during unwanted pregnancy. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 38(11): 2844–2852, 2014.

Rudd, R.A.; Seth, P.; David, F.; and Scholl, L. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2010–2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 65(50–51): 1445–1452, 2016.

Sampson, H.W. Alcohol and other factors affecting osteoporosis risk in women. Alcohol Research & Health 26(4): 292–298, 2002.

Schoenborn, C.A.; and Gindi, R.M. Electronic Cigarette Use Among Adults: United States, 2014. NCHS Data Brief, No. 217. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2015.

Shiono, P.H.; Klebanoff, M.A.; Nugent, R.P.; Cotch, M.F.; Wilkins, D.G.; Rollins, D.E.; Carey, J.C.; and Behrman, R.E. The impact of cocaine and marijuana use on low birth weight and preterm birth: A multicenter study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 172(1): 19–27, 1995.

Smith, K. and Lipari, R.N. Women of childbearing age and opioids. The CBHSQ Report, January 17, 2017. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2017.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality [formerly Office of Applied Studies]. The NSDUH Report: Concurrent Illicit Drug and Alcohol Use. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2009a.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Substance Abuse Treatment: Addressing the Specific Needs of Women. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 51, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4426. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2009b.

Thom, B. Sex differences in help-seeking for alcohol problems entry into treatment. British Journal of Addiction 82(9): 989–997, 1987.

Tolia, V.N.; Patrick, S.W.; Bennett, M.M.; Murthy, K.; Sousa, J.; Smith, P.B.; Clark, R.H.; and Spitzer, A.R. Increasing incidence of the neonatal abstinence syndrome in the U.S. neonatal ICUs. New England Journal of Medicine372: 2118–2126, 2015.

Tsai, J.; Floyd, R.L.; Green, P.P.; Denny C.H.; Coles, C.D.; and Sokol, R.J. Concurrent alcohol use or heavier use of alcohol and cigarette smoking among women of childbearing age with accessible health care. Prevention Science 11(2): 197–206, 2010.

Urbano-Marquez, A.; Estruch, R.; Fernandez-Sola, J.; Nicolas, J.M.; Pare, J.C.; and Rubin, E. The greater risk of alcoholic cardiomyopathy and myopathy in women compared with men. Journal of the American Medical Association 274(2): 149–154, 1995.

U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2011 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute, U.S.Department of Health and Human Services, 2014. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/uscs.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Women’s Health USA 2013. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2013. Available at: http://mchb.hrsa.gov/whusa13/health-status/health-behaviors/p/illicit-drug-use.html.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020 Topics & Objectives: Maternal, Infant, and Child Health. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/maternal-infant-and-child-health/objectives.

Villapiano, N.L.G.; Winkelman, T.N.A.; Kozhimannil, K.B.; Davis, M.M.; and Patrick, S.W. Rural and urban differences in neonatal abstinence syndrome and maternal opioid use, 2004 to 2013. JAMA Pediatrics 171(2): 194–196, 2017.

Vineis, P.; Alavanja, M.; Buffler, P.; Fontham, E.; Franceschi, S.; Gao, Y.T.; . . . Doll, R. Tobacco and cancer: Recent epidemiological evidence.Journal of the National Cancer Institute 96(2): 99–106, 2004.

Volkow, N.D.; Baler, R.D.; Compton, W.M.; and Weiss, S.R.B. Adverse health effects of marijuana use.New England Journal of Medicine 370: 2219–2227, 2014.

Warren, K.R.; Hewitt, B.G.; and Thomas, J.D. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: Research challenges and opportunities. Alcohol Research & Health 34(1): 4–14, 2011.

White, A.; Castle, I.-J. P.; Chen, C. M.; Shirley, M.; Roach, D.; and Hingson, R. Converging patterns of alcohol use and related outcomes among females and males in the United States, 2002 to 2012. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 39: 1712–1726, 2015.

World Health Organization. Women’s Health. [Fact sheet.] Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2013. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs334/en/.

World Health Organization. Information Sheet on Opioid Overdose. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2014. Available at: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/information-sheet/en/.

List of Figures

Figure 1-1. Prevalence of any drinking, binge drinking, and heavy drinking in the past 30 days among females ages 15–44, 2002–2015.

Figure 1-2. Prevalence of any drinking, binge drinking, and heavy drinking in the past 30 days among females ages 15–44, by age group, 2002–2015.

Figure 1-3. Prevalence of any drinking, binge drinking, and heavy drinking in the past 30 days among females ages 15–44, by race/Hispanic origin, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Figure 2-1. Prevalence of cigarette use, any illicit drug use, marijuana use, and nonmedical use of prescription drugs in the past 30 days among females ages 15–44, 2002–2015.

Figure 2-2. Prevalence of cigarette use, any illicit drug use, marijuana use, and nonmedical use of prescription drugs in the past 30 days among current drinkers, females ages 15–44, 2002–2015.

Figure 2-3. Prevalence of cigarette use, any illicit drug use, marijuana use, and nonmedical use of prescription drugs in the past 30 days among current drinkers, females ages 15–44, by age group, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Figure 2-4. Prevalence of cigarette use, any illicit drug use, marijuana use, and nonmedical use of prescription drugs in the past 30 days among current drinkers, females ages 15–44, by race/Hispanic origin, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Figure 3-1. Prevalence of alcohol and illicit drug abuse and dependence in the past 12 months among females ages 15–44, 2002–2015.

Figure 3-2. Prevalence of alcohol and illicit drug abuse and dependence in the past 12 months among females ages 15–44, by age group, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Figure 3-3. Prevalence of alcohol and illicit drug abuse and dependence in the past 12 months among females ages 15–44, by race/Hispanic origin, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Figure 3-4. Prevalence of alcohol and illicit drug abuse and dependence in the past 12 months among current drinkers, females ages 15–44, 2002–2015.

Figure 4-1. Prevalence of need for treatment for alcohol use and illicit drug use and percentage for not receiving treatment among those who needed treatment in the past 12 months, females ages 15–44, 2002–2015.

Figure 4-2. Prevalence of need for treatment for alcohol use and percentage for not receiving treatment among those who needed treatment in the past 12 months, females ages 15–44, by age group, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Figure 4-3. Prevalence of need for treatment for alcohol use and percentage for not receiving treatment among those who needed treatment in the past 12 months, females ages 15–44, by race/Hispanic origin, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Figure 4-4. Prevalence of need for treatment for illicit drug use and percentage for not receiving treatment among those who needed treatment in the past 12 months, females ages 15–44, by age group, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Figure 4-5. Prevalence of need for treatment for illicit drug use and percentage for not receiving treatment among those who needed treatment in the past 12 months, females ages 15–44, by race/Hispanic origin, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

List of Tables

Table 1-1. Prevalence of substance use, abuse, and dependence among females ages 15–44, 2002–2015.

Table 1-2. Prevalence of any drinking, binge drinking, and heavy drinking in the past 30 days among females ages 15–44, by age group, 2002–2015.

Table 1-3. Prevalence of any drinking, binge drinking, and heavy drinking in the past 30 days among females ages 15–44, by race/Hispanic origin, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Table 1-4. Prevalence of any drinking and binge drinking in the past 30 days among females ages 15–44, by pregnancy status and age group, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Table 2-1. Prevalence of cigarette use, any illicit drug use, marijuana use, and nonmedical use of prescription drugs in the past 30 days among current drinkers, females ages 15–44, by age group, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Table 2-2. Prevalence of cigarette use, any illicit drug use, marijuana use, and nonmedical use of prescription drugs in the past 30 days among current drinkers, females ages 15–44, by race/Hispanic origin, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Table 3-1. Prevalence of alcohol and illicit drug abuse and dependence in the past 12 months among females ages 15–44, by age group, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Table 3-2. Prevalence of alcohol and illicit drug abuse and dependence in the past 12 months among females ages 15–44, by race/Hispanic origin, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Table 3-3. Prevalence of alcohol and illicit drug abuse and dependence in the past 12 months among current drinkers, females ages 15–44, by age group, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Table 3-4. Prevalence of alcohol and illicit drug abuse and dependence in the past 12 months among current drinkers, females ages 15–44, by race/Hispanic origin, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Table 4-1. Prevalence of need for treatment for alcohol use and illicit drug use and percentage for not receiving treatment among those who needed treatment in the past 12 months, females ages 15–44, by age group, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Table 4-2. Prevalence of need for treatment for alcohol use and illicit drug use and percentage for not receiving treatment among those who needed treatment in the past 12 months, females ages 15–44, by race/Hispanic origin, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Figure 1-1. Prevalence of any drinking, binge drinking, and heavy drinking in the past 30 days among females ages 15–44, 2002–2015.

Data for Figure 1-1 are presented in Table 1-1.

Figure 1-2. Prevalence of any drinking, binge drinking, and heavy drinking in the past 30 days among females ages 15–44, by age group, 2002–2015.

Data for Figure 1-2 are presented in Table 1-2.

Figure 1-3. Prevalence of any drinking, binge drinking, and heavy drinking in the past 30 days among females ages 15–44, by race/Hispanic origin, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Data for Figure 1-3 are presented in Table 1-3.

Figure 2-1. Prevalence of cigarette use, any illicit drug use, marijuana use, and nonmedical use of prescription drugs in the past 30 days among females ages 15–44, 2002–2015.

Data for Figure 2-1 are presented in Table 1-1.

Figure 2-2. Prevalence of cigarette use, any illicit drug use, marijuana use, and nonmedical use of prescription drugs in the past 30 days among current drinkers, females ages 15–44, 2002–2015.

Data for Figure 2-2 are presented in Table 1-1.

Figure 2-3. Prevalence of cigarette use, any illicit drug use, marijuana use, and nonmedical use of prescription drugs in the past 30 days among current drinkers, females ages 15–44, by age group, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Data for Figure 2-3 are presented in Table 2-1.

Figure 2-4. Prevalence of cigarette use, any illicit drug use, marijuana use, and nonmedical use of prescription drugs in the past 30 days among current drinkers, females ages 15–44, by race/Hispanic origin, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Data for Figure 2-4 are presented in Table 2-2.

Figure 3-1. Prevalence of alcohol and illicit drug abuse and dependence in the past 12 months among females ages 15–44, 2002–2015.

Data for Figure 3-1 are presented in Table 1-1.

Figure 3-2. Prevalence of alcohol and illicit drug abuse and dependence in the past 12 months among females ages 15–44, by age group, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Data for Figure 3-2 are presented in Table 3-1.

Figure 3-3. Prevalence of alcohol and illicit drug abuse and dependence in the past 12 months among females ages 15–44, by race/Hispanic origin, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Data for Figure 3-3 are presented in Table 3-2.

Figure 3-4. Prevalence of alcohol and illicit drug abuse and dependence in the past 12 months among current drinkers, females ages 15–44, 2002–2015.

Data for Figure 3-4 are presented in Table 1-1.

Figure 4-1. Prevalence of need for treatment for alcohol use and illicit drug use and percentage for not receiving treatment among those who needed treatment in the past 12 months, females ages 15–44, 2002–2015.

Data for Figure 4-1 are presented in the following page.

Figure 4-2. Prevalence of need for treatment for alcohol use and percentage for not receiving treatment among those who needed treatment in the past 12 months, females ages 15–44, by age group, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Data for Figure 4-2 are presented in Table 4-1.

Figure 4-3. Prevalence of need for treatment for alcohol use and percentage for not receiving treatment among those who needed treatment in the past 12 months, females ages 15–44, by race/Hispanic origin, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Data for Figure 4-3 are presented in Table 4-2.

Figure 4-4. Prevalence of need for treatment for illicit drug use and percentage for not receiving treatment among those who needed treatment in the past 12 months, females ages 15–44, by age group, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Data for Figure 4-4 are presented in Table 4-1.

Figure 4-5. Prevalence of need for treatment for illicit drug use and percentage for not receiving treatment among those who needed treatment in the past 12 months, females ages 15–44, by race/Hispanic origin, 3-year moving annual averages, 2002–2015.

Data for Figure 4-5 are presented in Table 4-2.